Abolish Tenure, and Replace it with a 40 Hour Work Week

Originally published on the blog, July 1

This is part of a series of posts on the abuse of power inherent to academia as a profession, and what we could do to reimagine and rebuild a more just, anti-racist university. Read parts one and two.

Although I have tenure now, as a new, African American faculty member I know I was strongly advised by my senior colleagues and administrators to keep my service to that so-called diversity mission to a minimum, and it was advice that I was happy to follow. I was happy to follow that advice even if it meant keeping as low a profile as possible and declining requests to take on important projects that I knew would not count when I came up for tenure. I’m not sure what choices I would make now.

“What Is Faculty Diversity Worth to a University?” Patricia A. Matthew, NOVEMBER 23, 2016,

When ever I meet up with friends or colleagues who are tenured academics these days, I’m struck by a rather depressing fact. They are all miserable.

It’s so disheartening! As bad as it is to be locked out of academia, it doesn’t seem all that much better to finally get the thing you’ve been struggling for all your adult life, only to find it sucks.

But apparently this is the case. Finally making it to that coveted position rarely seems to signal the end of the fear and stress inherent to pre-tenure life.

From the University of Copenhagen’s magazine, March 2017. Seriously, though – I was recently at a conference talking to an anthropologist whose biological anthropologist colleague announced he had published a book supporting CREATIONISM the week after he got tenure.

I assume this is because, once you finally get tenure, it’s hard to drop the habits and dispositions that have shaped your entire professional life up to that point. You’ve spent the first two decades of your career trying hard not to rock the boat. Sticking to a strategic publishing plan. Not saying or researching anything too ‘out there’ until you have tenure. All with the implicit promise that once your tenure confirmation letter comes through, you will finally have this magical ‘academic freedom’ that everyone talks about, where you will finally get to say and do what you want.

But then when people do finally get tenure, it seems hard to undo those habits of cautionary self-doubt. Add that to the survivor’s guilt and imposter-syndrome ingrained into those who actually make it through the academic job market and land a TT job, it’s difficult to imagine anyone would suddenly emerge ready to speak their mind without fear.

It is ridiculous to give anyone a guaranteed job for life

I once worked for a professor who was a very senior university administrator. One afternoon, she was fired – without any warning – by the president of the university.

It was shocking and dramatic ending to a long career. The man who had been her staunch supporter and promoter was also fired. Their respective decades of university service came to an end in a single afternoon.

But it was 100% the right thing to do. This woman was a horrible, nasty, vindictive, racist bully, who terrorized and belittled her students, colleagues, and employees.

The weird thing was, however, that although she lost her very well paid administrative position, she was still a tenured faculty member. So even though she was a vindictive, racist bully, she was able to stay in her department — and resume teaching.

Looking back over my shoulder as I ran, ran, ran for the hills, I felt sorry for all the predominantly first gen, low-income, students of color who would now be required to take classes from her.

She’s still there now. Still teaching.

Tenure isn’t protecting the people who need it the most

Oh, McSweeney’s. Those are tears of laughter, honest, not despair.

There are certainly examples of professors whose tenured status protected them from being fired for doing politically unpopular work.

But I would argue these are examples are the exception, not the rule. More scholars are prevented from doing political and controversial work by the tenure-system, than protected. Like the African American scholar Patricia A. Mathews, quote above, who are warned away from for doing politically relevant work, all in the pursuit of ‘tenure’.

The academic freedom cases that tend to be publicized are those that involve an individual standing up against right-wing non-academic critics. But the harm done by the tenure-system is insidious and mundane, and comes from our mentors, colleagues, and friends. It also disproportionately impacts those who already have less power, such as BIPOC scholars and women.

What is the point of tenure, if a female professor has to warn her students not to get too close to her male colleague, rather than telling that colleague to stop hitting on his students? Or a white professor feels she can’t call out a racist colleague in a faculty meeting?

I have, on occasion, asked tenured professors about this, specifically in relation to men known to creep on students or senior male faculty known to be actively discriminating against female job applicants.

“Why is it so hard not to just tell your colleague to stop? You have tenure. Why not call him out?”

They tell me they don’t do so because they are scared.

Tenure means staying at one institution until you retire (or die). Professors know they are stuck with this particular group of people for the rest of their careers. Calling them out, even for egregious bullying, won’t result in them losing their jobs. And an angry colleague has the power to make their own lives hell.

So they “choose their battles”. Which, incidentally, rarely involve sticking their necks out for people of color. Or against sexual predators. People who, it turns out, really benefit from the protections of tenure.

Taking away teaching responsibilities is not punishment

I am so sick of this scenario:

A male tenured professor is caught sexually harassing students, and his department head or Dean responds by limiting his contact with students. He isn’t fired, because he can’t be; instead his teaching and advising responsibilities are taken away from him, and this is meant to be a punishment.

When it came to light that Gary Urton was propositioning students for sex in exchange for grades, Harvard’s initial response was to fire him from his position as Director of Undergrad Studies. Which is… not so great, when you realize that this service work would now be done by his junior, female colleagues.

In a world where most faculty prefer doing research to teaching anyway, removing teaching and student-facing service work is no punishment. It’s like giving someone a research sabbatical!

There is a quick and simple fix we could make. If someone is removed from working with students, their salary should be docked to reflect this fact.

If teaching is meant to be 50% of their job as a tenured faculty member, their salary and benefits should drop by 50% when they can no longer be trusted to do that job without harming their students.

Give professors explicit job descriptions, and hold them to it

The problem is, it would be difficult to figure out how much of someone’s pay ought to be taken away from them. Many faculty are hired without explicit contracts laying out what percentage of their time should be spent on teaching, research, service, and pubic outreach.

Giving faculty explicit contracts that include percentage time allocations could fix this. Specify what their work hours are, what percentage of their time should spent on each aspect of their job, and then – if they prove themselves to be unfit to do one aspect of their job – their hours and salary should be reduced to reflect that.

This likely makes you feel uncomfortable, and I understand.

There is, at this point in time, a flourishing cross-disciplinary body of literature dedicated to analyzing the negative consequences of neoliberalizing higher education. In Europe, at least, this is specifically tied to New Public Management (NPM), which aimed to recomceptualize and organize universities along the lines of corporations, positioning faculty as corporate-esque employees.

It is very hard to have a conversation about ending tenure without being accused of promoting the further neoliberalization of universities. (For the record, and in case there was any confusion, I am very much against the neoliberalization of universities.)

But I bet you that, for every senior academic who complains about the overreach of administrator oversight in academia, there are an army of potential scholars dropping out as undergrads, grad students, postdocs, or junior level, because they were bullied, harassed, or assaulted by people in power who couldn’t be fired.

I’ll also bet you that, for every senior academic who writes scathing articles condemning the death of academic freedom, there is at least one junior colleague afraid to call out their senior colleague’s racist/sexist/classist micro-aggressions during faculty meetings.

The consequences of harassment and bullying on the part of faculty should be clear and painful, up to and including being fired.

We have to find a way to talk about this, because protecting bullies in the name of academic freedom is madness. There is the middle-ground between the Thatcherite dreams of academics as purely market-based knowledge-economy metrics-producing robots, and the current system of continuing to pay salaries to unaccountable tyrants and predators.

What should that job description include, anyway?

Having explicit job descriptions would help in other ways, and specifically it would help faculty of color, and female faculty, who carry the burden of the unvalued, uncompensated service/administrative work in academia, particularly “diversity” work.

I was struck when reading the #BlackInTheIvory twitter posts, by ones like this:

Link to original

Or this:

Link to original

There is a real tension between the desire to promote research that will ‘have an impact’ beyond the academy, or actually be read/taken seriously by the wider public. And the reality whereby scholars who try to do meaningful, engaged work are accused of being ‘activists’ or ‘publicity seekers’.

If we want to pay more than lip-service to the idea of community outreach, it should be written into job contracts that a specified percentage of time is devoted to engaged, activist work. And again: people should be held to it.

Specifying job descriptions could resolve some of this tension.

The rule that you shouldn’t do the experimental or controversial work until you have tenure doesn’t just cause individual self doubt; it actively stifles innovation and encourages conservatism. It stops us from being able to reimagine the academy as something more than it currently is.

That means not only that younger scholars are less likely to experiment with interesting and novel method or ideas. But also that we are failing to explore all the possible kinds of work that academics could be doing. Why shouldn’t an academic job involve activism? Working for one’s community? Engaging in action that makes our research relevant and worthwhile?

Specifying percentages – and sticking to them – would also be a way to compare contracts/workloads. Holding men, and white people, accountable for their failure to do as much as their colleagues.

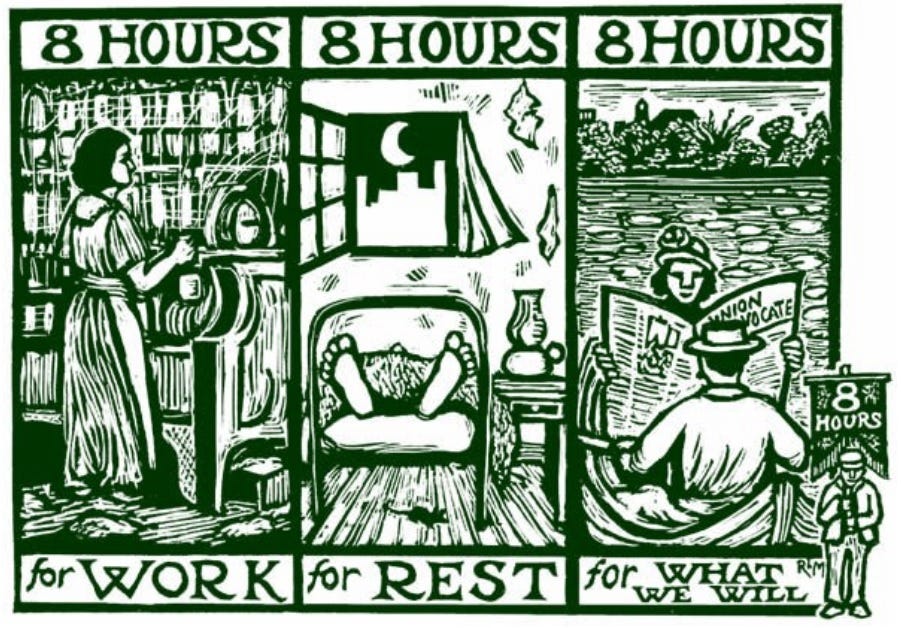

The 40 hour work week

Why is a 40 hour work week something we’d fight for other workers to get, but not ourselves?

But I can hear your argument against this.

It’s crazy, and insulting, to propose adding more things to academic job descriptions. Everyone is already over-worked. 60+ hour work weeks are normal, even valorized. Mary Beard apparently works 100 hour weeks (and is probably not unusual).

No one really believes this leads to better research or teaching: quite the opposite. So why not just work reasonable hours?

This is a very complicated issue, that relates to the status of academia as an elite profession, and a vocation or lifestyle, rather than ‘a job’. There are real, concrete reasons why people don’t want to think about academia as just a job.

But the irony is, academia would be so much more enjoyable, productive, and equitable a career, if we did treat it like a job!

Being able to work reasonable hours, and to have clear job descriptions that laid out what our roles were, would be one of those advantages. My proposal, then, is a radical one. Rather than adding yet another set of tasks to an already exhausted workforce, let’s rethink it all completely.

A forty hour work week means 8 hour days, 5 days a week. That’s not a lot of time… Forcing ourselves to work these hours would force us to really specify what our priorities are, for academic work. To be explicit about what we think a university should be, and be for.

If we think the research we do and knowledge we produce has significance, and should be taken seriously by policy makers or specific publics (medical profession, legal profession, journalists, etc.), then we should be specifying in our contracts that a percentage of our time is devoted to learning those skills and doing that work.

If teaching is important, all the different tasks involved in teaching and mentoring should be accounted for, not just in-class hours. So answering emails, doing office hours, reading student drafts and papers, course prep. Also, time spent being trained how to work with specific student populations, such as students with disabilities, students of color, and working class students.

Weirdly, to do this, we would have to accept doing less not more. Fewer publications. Smaller research projects. Teaching fewer students. Or alternatively, embracing specialization and making it a level-playing field in terms of compensation and prestige. Faculty who only do research are already a reality in STEM fields; faculty who only teach exist everywhere (but are just not given fair contracts).

So what do you think? Would you give up the ‘freedom’ of tenure, in exchange for a 40 hour work week and normal job benefits?